Almost 60 years ago now, the United States enacted the first automobile emissions standards the world had ever seen.

Mainly concerned about smog in Los Angeles, regulators set thresholds intended to limit the amount of pollutants released into the atmosphere by automobiles. Year after year, the thresholds increased, targeted pollutants expanded, and governments worldwide began adopting emission standards of their own.

Today, after 196 countries negotiated the Paris Agreement in 2015, there is hardly a country left without some form of emissions regulation.

Since 1966, the primary method for reducing pollution from a combustion engine has always been by way of the catalytic converter.

It is widely known that for a catalytic converter to do its job, it needs some platinum group metals (PGMs) such as platinum, palladium, and rhodium to convert the harmful gases produced by vehicles into relatively harmless ones before being released into the atmosphere.

Two years ago, ResearchandMarkets.com published a market study forecasting that,

“The catalytic converter market is projected to grow from USD 42.4 billion in 2018 to USD 73.1 billion by 2025, at a CAGR of 8.10%”.

So, as the market for catalytic converters grows, demand for PGMs has followed suit.

For years, platinum was the most-used of all PGMs in automobile catalytic converters. It wasn’t until the early 2000s, when palladium cost less than half the price of platinum, that automakers opted for palladium as a fully functional substitute.

Since then, they continue to use palladium-based catalytic converters in gas-powered vehicles. Diesel engines continued using platinum-based catalytic converters, which kept platinum in high demand… until ‘dieselgate’.

In September 2015, the United States Environmental Protection Agency served a notice of violation to Volkswagen Group for cheating on emissions tests of its diesel cars in the U.S., leading to a recall of all Volkswagen cars registered and sold in the U.S. between 2009 and 2015.

Naturally, this had a serious knock-on effect for platinum demand, sinking the metal’s price to its 13-year low that same year.

Palladium Price Main Benefactor to More Stringent Emission Requirements

In the meantime, the palladium price continued to climb higher. Note that, of the two metals, platinum is more available than palladium. With diesel cars taking a hit globally, demand for gasoline-powered vehicles increased substantially, leading to higher demand for palladium that was already in short supply.

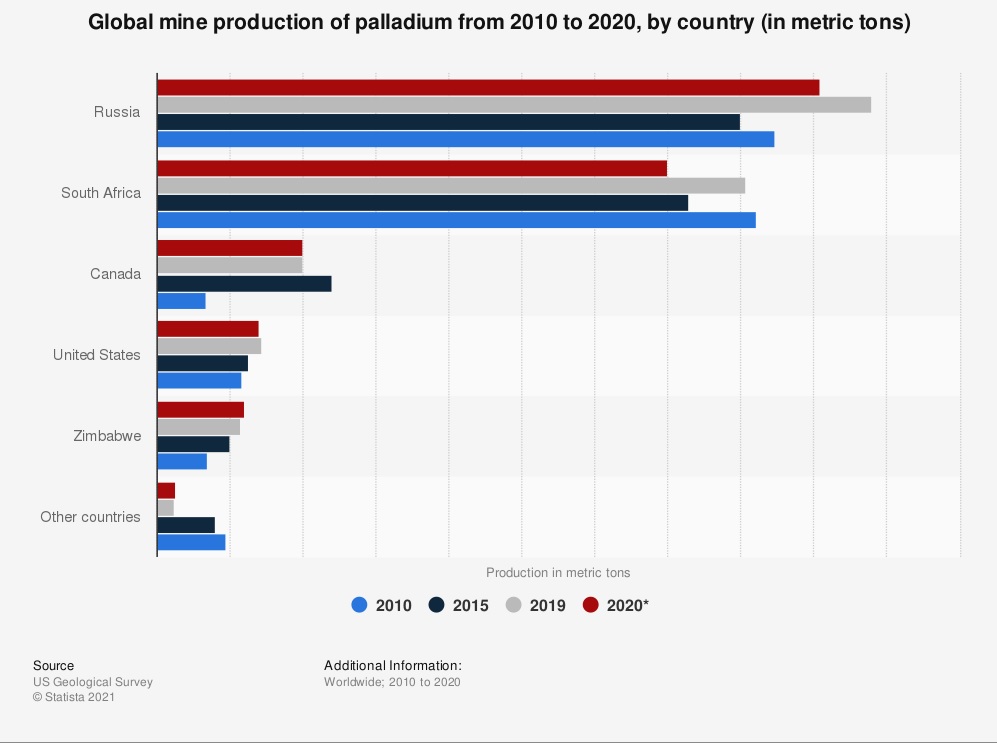

The Statista chart below shows global production of palladium by country and how they struggle to grow (or maintain) production levels from year to year.

One can see that Russia and South Africa dominate production.

Automobile production and PGM prices

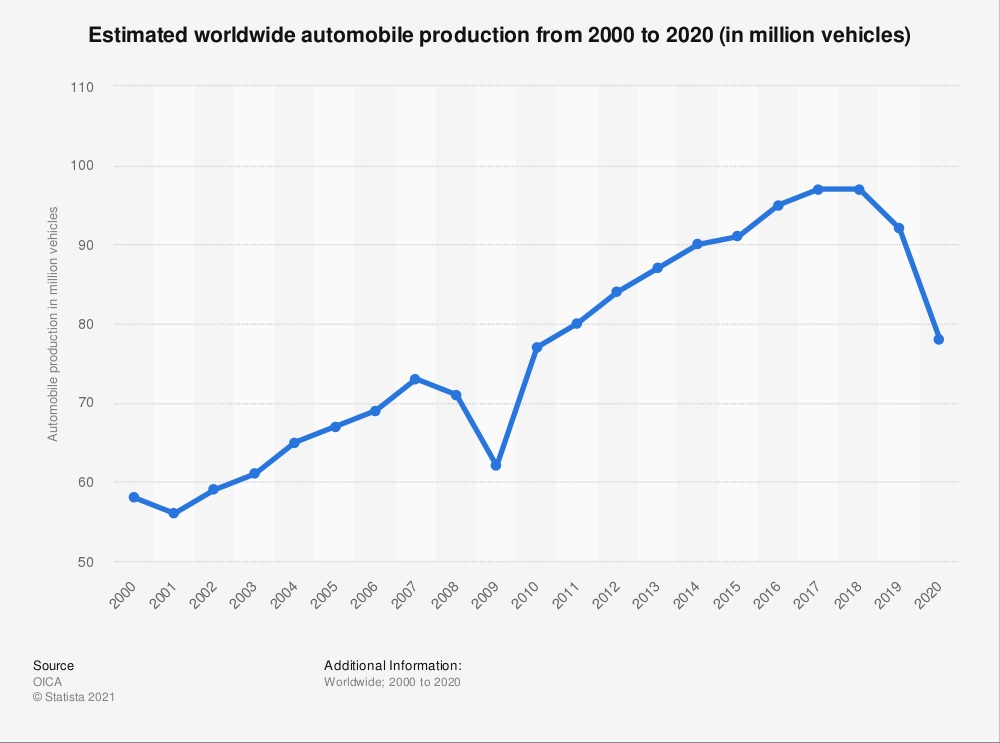

To properly understand the main driver behind palladium’s price surge, we need to look at automobile production levels and the direction they are headed.

According to Statista, global automobile production has been on the decline since 2019. See the chart below for a picture of the pace of decline:

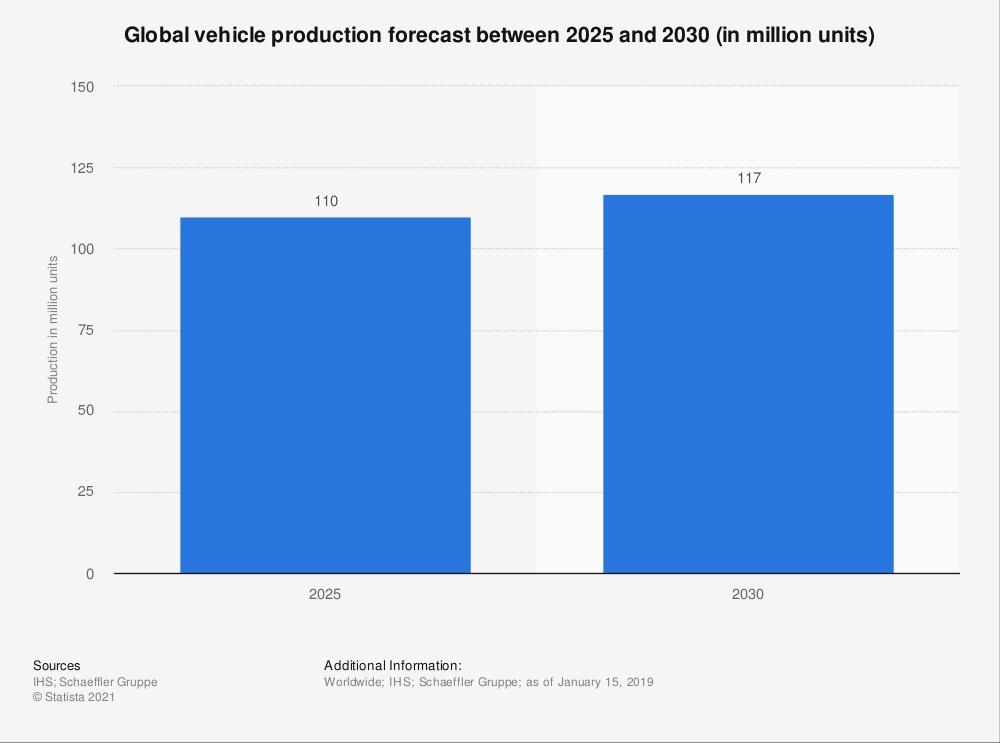

Automobile production levels are expected to pick up again globally by 2025. Statista projects that 110 million vehicles will be produced by 2025.

However, of interest to us when it comes to palladium is the forecast for gas-powered vehicle production globally.

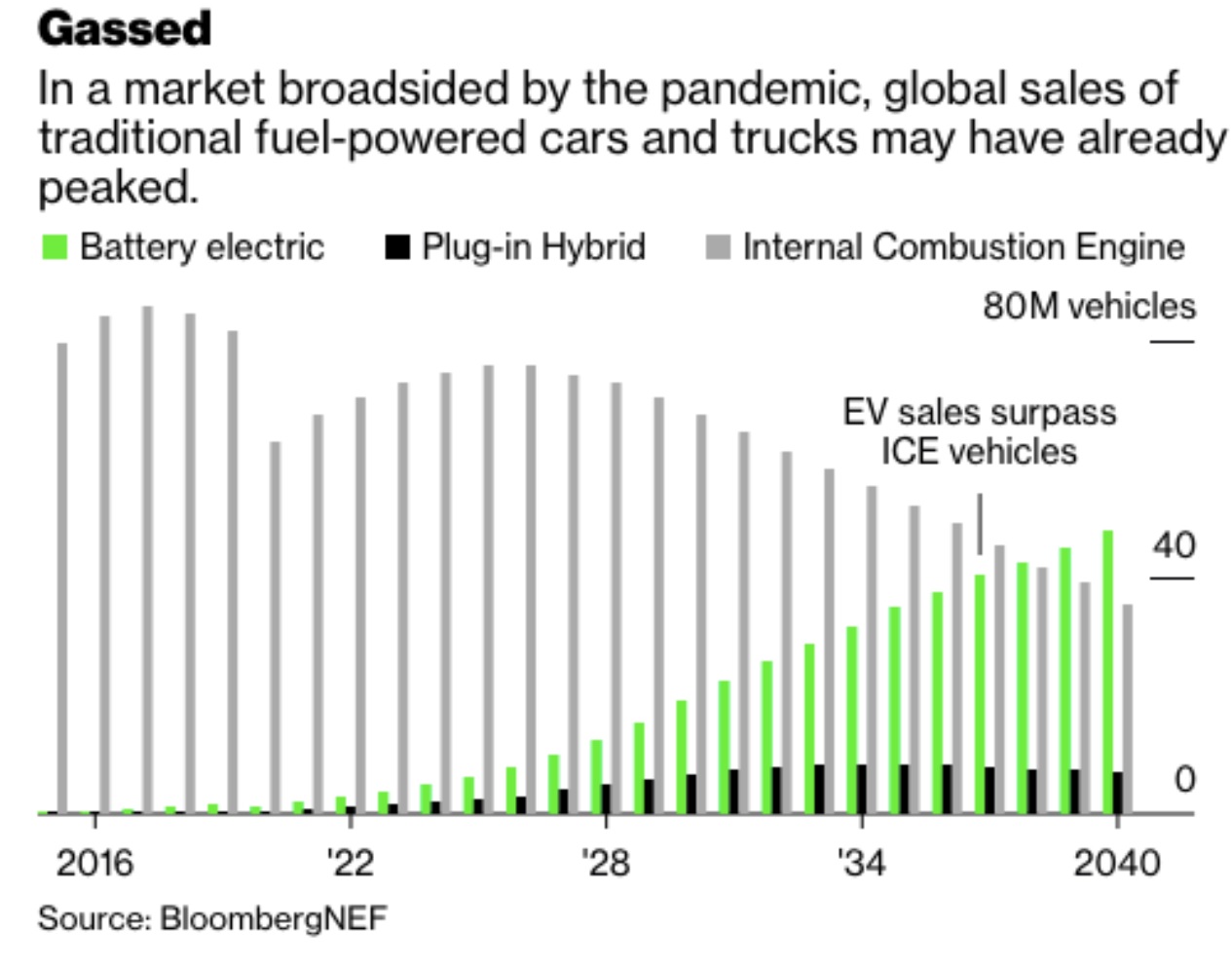

Bloomberg released this chart of projected sales of gas-powered cars, as well as hybrid and electric vehicles.

Source: Bloomberg

Source: Bloomberg

The chart illustrates that sales of gas-powered vehicles peaked in 2018 and took a beating in 2020. Sales for gas-powered vehicles are projected to pick up again between 2021 and 2025, before starting a gradual decline until EVs take over around 2039.

Given the relatively short-term future for palladium’s most critical use, why the continued hikes in prices of the metal?

The short answer: hyper-demand

Who doesn’t want Palladium?

Even though production and sales of new gas-powered cars are down globally, Europe and North America continue to require palladium in all vehicles as part of emissions regulations. In fact, after the 2015 Paris Agreement, more palladium will now be necessary, as many governments target more aggressive emission levels for the future.

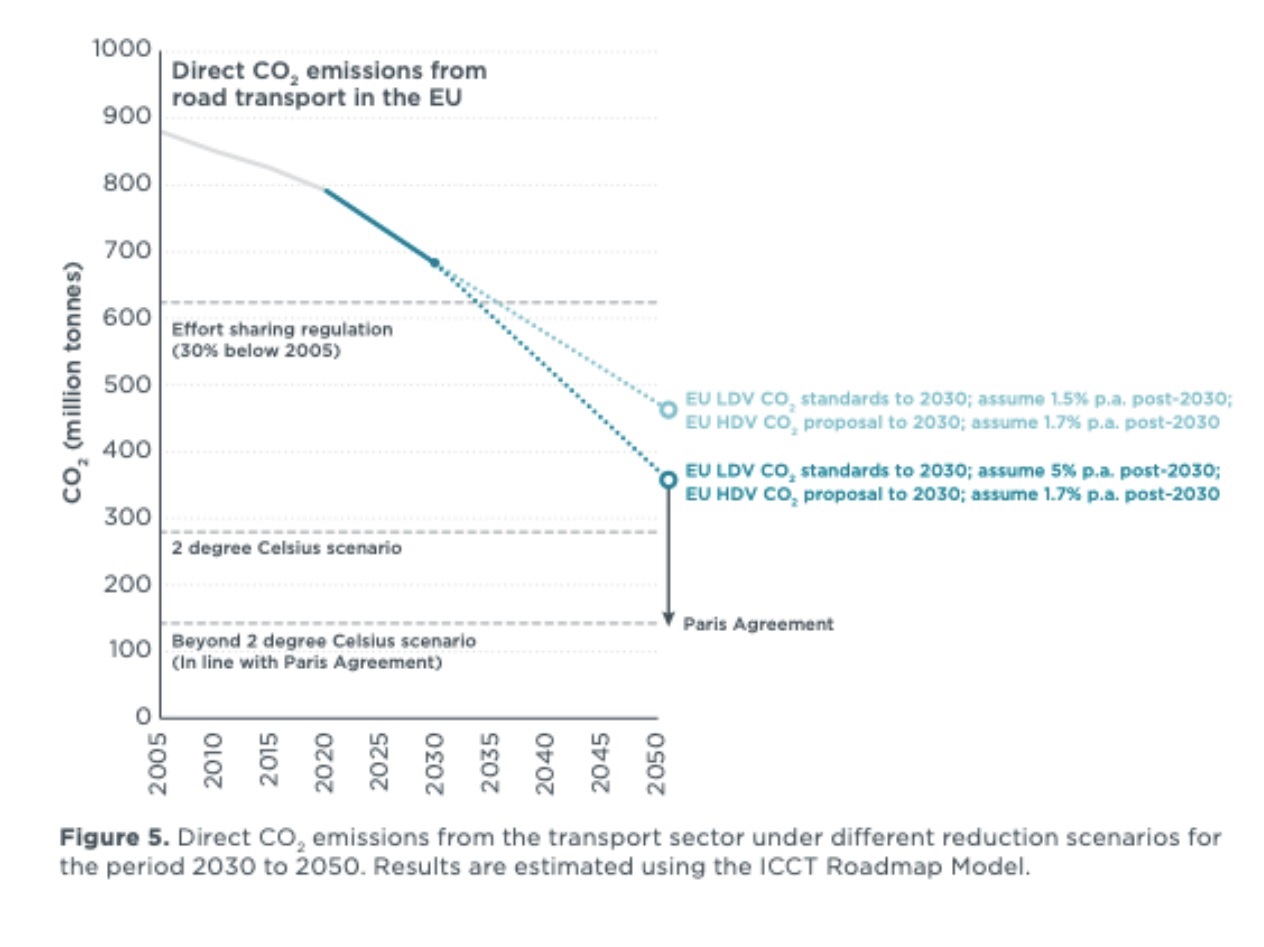

The ICCT reports that in Europe,

“New car CO2 emissions, on average, have to reduce by 15% by 2025 and by 37.5% by 2030, relative to a 2021 baseline. Expressed in NEDC terms, using the current 2021 CO2 target of 95 g/km as the baseline, these reductions would translate into a target value of 81 g/km (2025) and 59 g/km (2030)”

The curve below shows how steep the rate of change needs to be for Europe to hit its targets vis-à-vis the Paris Agreement.

In Canada and the U.S., the trend is no different.

The ICCT reported that,

“On May 30, 2018, Canada published final standards to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from new on-road heavy-duty vehicles. The new regulation is part of Canada’s economy-wide commitment to reduce GHG emissions 30% by 2030 compared to a 2005 baseline. This new round of requirements applies to model year (MY) 2021 through 2027 trucks and buses and MY 2020 through 2027 commercial trailers.”

As regulators tighten the screws on emission levels, automakers will require more and more palladium to manufacture compliant vehicles in today’s market.

China VI and BS VI

The global automotive industry is likely facing one of the toughest challenges in its history.

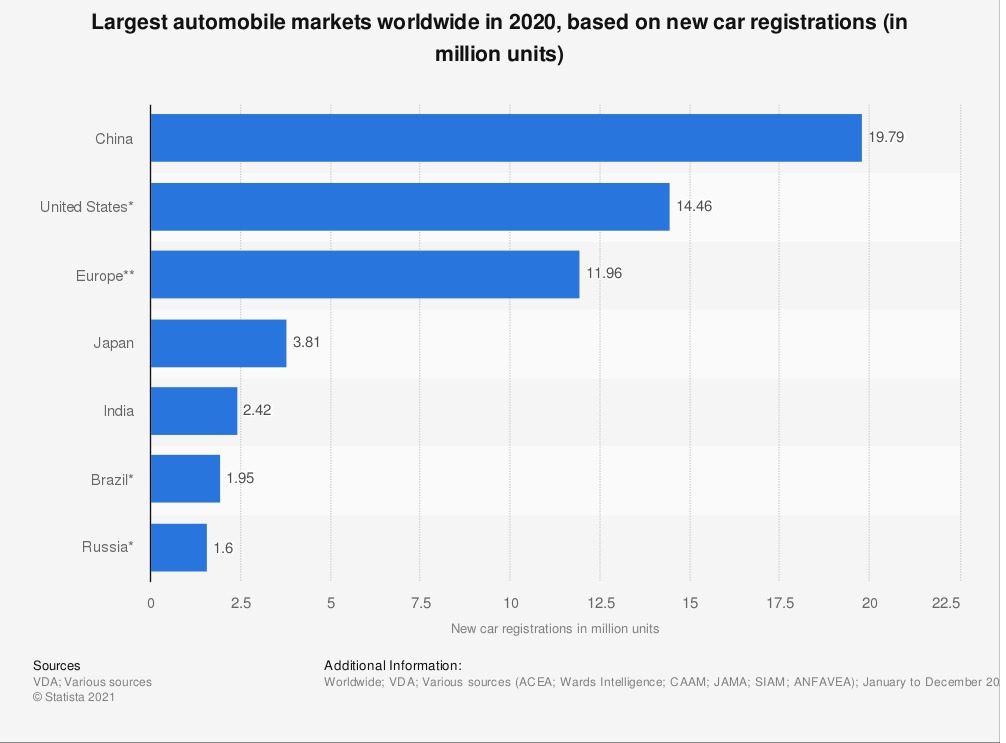

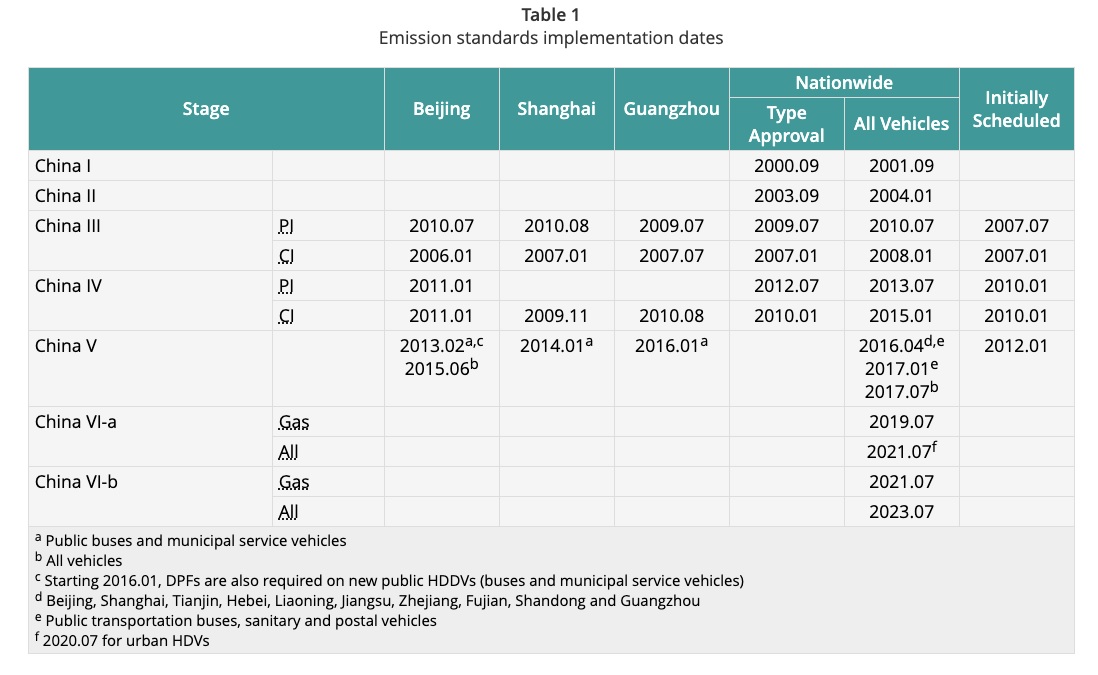

On January 1, 2021, China, the world’s largest automobile market, entered the strictest phase of its emissions reduction plan. The DieselNet table below shows the different implementation stages and scheduled effective dates:

As of 2019, China was still in China IV and was scheduled to transition to China VI by 2020 until the government announced its decision to delay the implementation of China VI nationwide to January 1, 2021.

The Statista chart below shows just how much of the market China commanded last year.

With strict emissions controls now in effect nationwide, automakers must be wondering where on earth they can find the necessary palladium for every car they produce; if, of course, they want to pass an emissions test in China going forward.

Also note, although it’s only a fraction of the Chinese market, India is the fifth-largest automobile market in the world.

In India, it wasn’t until April 2020 that all vehicle manufacturers were required to produce, sell and register only BS VI compliant vehicles across the country. BS VI standards are similar to Euro 6 and China VI standards.

China and India are big drivers (and will continue to be for decades) behind the surge in demand for palladium and today’s near record-high price for the metal.

PGM Producers Expect Supply to Remain Tight This Year

Russia and South Africa are the world’s largest producers of palladium, followed by Canada and the U.S.

Together, Russia and South Africa were responsible for approximately 77% of all palladium produced worldwide in 2020 – with Russia accounting for 43.4% of global production.

At the beginning of the year, Nornickel, Russia’s biggest palladium producer, announced an expected 15-20% drop in output for 2021. On March 16, 2021, Reuters reported that:

“Nornickel expects its 2021 nickel, copper, platinum and palladium output to fall 15-20% short of original guidance due to waterlogging at two Siberian mines, the Russian company said on Tuesday.

The mines are unlikely to restart fully for another 3-4 months, the company said.”

Meanwhile, in South Africa, Argus media reported that supply is expected to be tight there as well,

“…in part because South Africa’s refiners are running below 100pc capacity amid the pandemic. Anglo American only restarted its converter plant A in December [2020] with its B plant still off line, weighing significantly on national PGM refining rates.”

Anglo American is South Africa’s largest PGM mining company.

Tharisa, another mining giant operating in South Africa, is also bracing for challenges ahead in 2021. The same Argus article reported that,

“Tharisa chief executive Phoevos Pouroulis said the return to work from the Christmas break has not been smooth, with Covid-19 rates rising in the country. ‘We know that a number of deep level mines have not been able to get up to full capacity after a month owing to the restrictions, people being affected and not returning to work,” he said. “You can never catch up that lost production or that lost time. It’s gone. So, I think there will be supply side challenges this year still from South Africa.'”

Despite being the most industrialized and technologically advanced country in Africa, South Africa has experienced tremendous turmoil and decline over the past decade.

According to Wikipedia, South Africa’s GDP peaked at,

“…$400 billion in 2011, but has since declined to roughly $283 billion in 2020.”

So, with countries worldwide implementing stricter emissions standards and key global producers projecting reduced output for 2021, you can expect the battle for palladium – and other PGMs – to intensify.

The Palladium Run

Within the last two weeks, palladium’s spot price leaped to its all-time high of USD 3,017 per ounce, beating last year’s record of USD 2,724.90 per ounce.

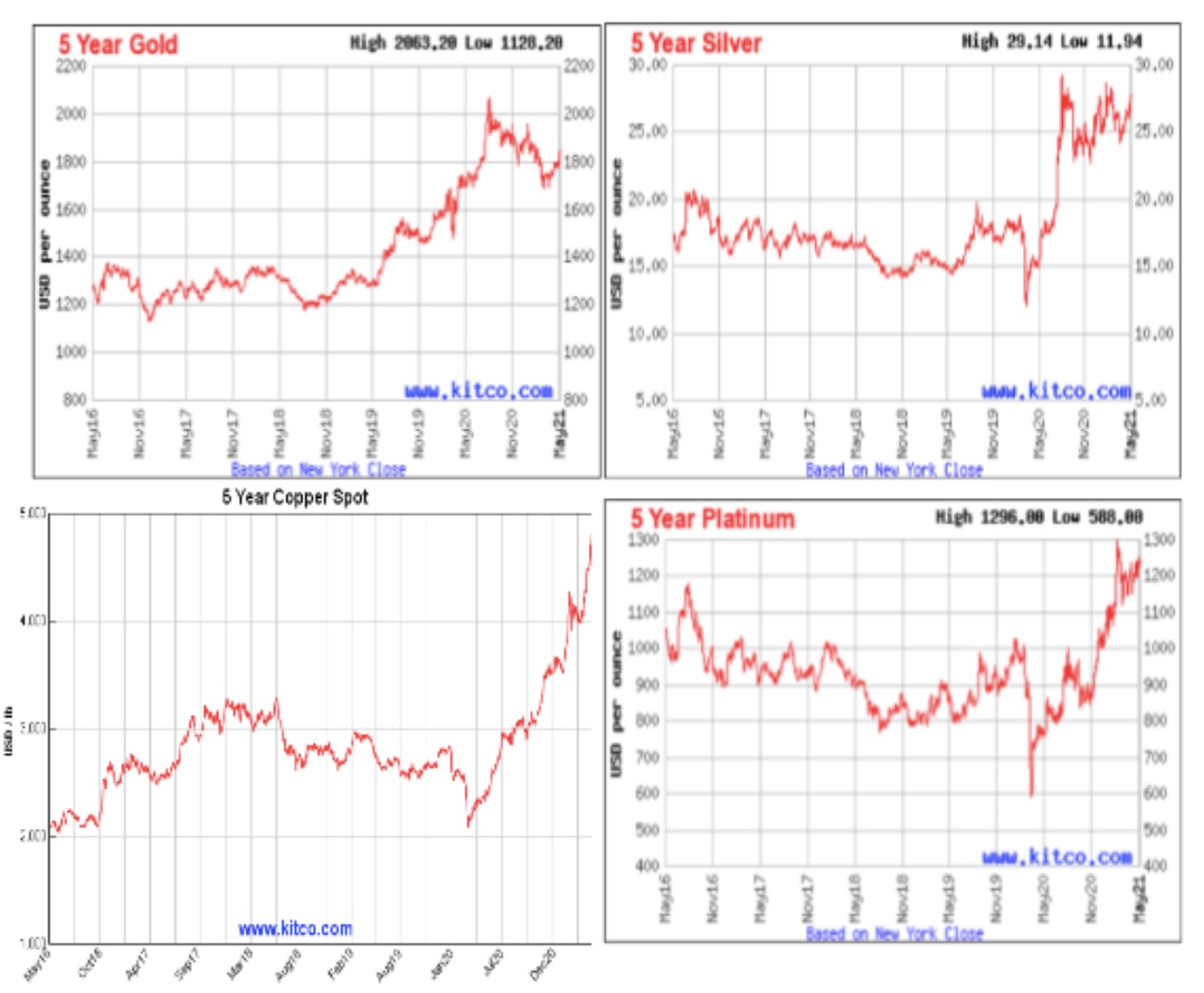

By far and away, it has outperformed almost every metal in a similar category over the last five years. See the charts below to compare palladium’s five year price versus its counterparts.

Source: KITCO

In the last five years, palladium’s return has been better than platinum, gold, silver, copper and the S&P 500, combined!

With a staggering return of approximately 367% in the last five years, only rhodium – the rarest and most valuable precious metal in the world – has yielded better returns than palladium.

But can it hold? Better yet, can it continue higher?

Two considerations:

First, with the price of palladium now more than doubling that of platinum, there is a chance automakers might be mulling over reverting to platinum as the metal of choice for gas-powered vehicles. However, as time is now of the essence, the cost of switching technologies to make this feasible may be too much for manufacturers to bear.

Secondly, the Bloomberg chart we referenced early on shows a steady increase in sales of gas-powered vehicles for the next four years. And as seen already, many governments have set aggressive targets in view of reaching minimal emissions levels by 2030. With this in mind, it seems reasonable for the price of palladium to remain elevated or even continue its upward trend for the next four years, maxing out sometime around 2025.

Palladium Price Remains Biggest Winner Among Metals

Despite the momentum behind many green metals, the biggest benefactor of the green movement – certainly in the last five years – has been palladium.

Given the world’s two most populous countries, China and India, are implementing stricter emissions standards, record palladium demand starts to make sense.

Furthermore, if the last 5-6 months is any indication of what the future holds, producers from Russia and South Africa will likely struggle to keep up with the pace of demand for palladium and other PGMs.

These factors present a bullish thesis for the palladium price, at least for the next 4-5 years, until gas-powered vehicles embark on their final journey to oblivion.

All the best with your investments,

PINNACLEDIGEST.COM

If you’re not already a member of our newsletter and you invest in TSX Venture and CSE stocks, what are you waiting for? Subscribe today. Only our best content will land in your inbox.